For many years, Scotland has produced some of the finest whiskeys the world has ever seen.

As such, I have come to not only appreciate the complexity and intricacies of a fine bottle of Scotch, but I’ve developed an adoration, nay, an obsession with Scotch whisky and its continual pursuit of perfection. It is my distinct privilege to have the opportunity to share my love of Scotch with you in this primer that will focus primarily on the world’s most beloved single malt Scotch whiskeys.

The History of Scotch Whisky

The first written mention of Scotch was found scribed on June 1st, 1495 in Volume X on page 487 of the Exchequer Rolls of Scotland where it reads “To Friar John Cor, by order of the King, to make aqua vitae VIII bolls of malt”. The Exchequer Rolls were records of all royal income and expenses. In this particular entry, it documents that Cor was given eight bolls of malt to make aqua vitae throughout the months of 1494. What this shows is that despite being the earliest written reference, distillation was well underway come the fifteenth century. If we only take into account the eight bolls given to Cor in 1494, we can estimate that 1500 bottles of whisky were produced that year.

Evolving from a Scottish drink called uisge beatha (meaning “water of life”), whisky began to circulate throughout the country, causing policymakers to begin taxing it come the year 1644. Unfortunately, despite the government’s attempt to regulate and draw income from such a popular drink, distillers began to sell it illegally and sales flourished across Scotland. By 1780 there were eight legal distilleries in all of Scotland competing against more than four hundred bootleg operations. By 1823 Parliament realized that in order for the legal producers to be able to compete with the pirates, they would have to ease restrictions and this decision is what gave birth to the famous ‘excise act’.

The popularity of whisky swelled again in 1831 with the invention of the column still. Now, thanks to new technology, distilleries were able to mass produce a smoother spirit at a significantly lesser cost.

Then in 1880, Scotch whisky became a global phenomenon thanks to a new microscopic insect that preyed on the grape vines in France. Since wine and brandy were considered two of the most popular drinks of the day, when the phylloxera bug began to destroy vineyards across France, wine and brandy production came to an almost immediate halt. With alcoholics around the world craving a substitute, the doors to the global marketplace opened wide for Scotland’s distillers and Scotch whisky became the world’s new popular drink.

Types of Scotch Whisky

There are two main types of Scotch whisky; single malt and single grain. From those two types, three subcategories are formed. Those categories are blended Scotch, blended malt Scotch, and blended grain Scotch.

Single Malt

Single malt Scotch whisky is today, the most popular choice in North American homes. This is an aged whisky made by a single distillery using only malted barley and water. It contains no other cereals and must be distilled, produced and bottled in Scotland.

Single Grain

Single grain Scotch whisky is less commonly found on the shelves of your local liquor store. It starts out with water and a malted barley but then has additional whole grains or cereals added to it which prevents it from complying with the laws that would permit it to be called single malt. Just like with single malt Scotch, it too has to be bottled in Scotland in order for it to be able to use the “Scotch” name. It is this type of Scotch that most blended Scotch whisky is made from.

Blended Scotch

A blended Scotch whisky is made from at least one or more single malt Scotch whiskeys that are blended together with a single grain Scotch whisky.

Blended Malt Scotch

A blended malt Scotch is actually one of the most uncommon types of Scotch that can be found today. Previously called a “vatted malt” or a “pure malt” it is when the blender takes two or more single malt Scotch whiskeys from at least two separate distilleries and blends them together to create one batch of whisky.

Blended Grain Scotch

A blended grain Scotch is similar to that of a blended malt, except it utilizes two or more single grain Scotch whiskeys from at least two separate distilleries. They are then blended together to create a single batch of whisky.

Double Malt Scotch

Many people have heard of a whisky referred to as a “double malt” Scotch. It should be noted that these do not actually exist. Whenever a bottle of single malt Scotch is referred to as “double malt” or “triple malt” it simply means that it was aged in two or more types of casks. The true term for this is double wood or triple wood. This is very common in the whisky world and despite being aged in multiple casks, it still remains in the single malt category.

The Name

While most consumers have a general understanding that Scotch whisky must always be from Scotland, few actually know the legal requirements behind naming a bottle of whisky “Scotch”.

The title of “Scotch” is defined and regulated by a document created on November 23, 2009, called the “Scotch Whisky Regulations 2009” or SWR. Not only regulating production, the act also governs the labeling, packaging and the advertising of Scotch whisky within the United Kingdom. The SWR is a complete replacement of the previous regulations which focused exclusively on the production process. While the SWR is technically only valid within its jurisdiction, international trade agreements have been put in place which effectively make some provisions of the SWR apply in countries outside the United Kingdom.

The document defines Scotch whisky in the following manner:

1: Must be produced at a distillery in Scotland from water and malted barley (to which only whole grains of other cereals may be added) all of which have been:

– Processed at that distillery into a mash

– Converted at that distillery to a fermentable substrate only by endogenous enzyme systems

– Fermented at that distillery only by adding yeast

– Distilled at an alcoholic strength by volume of less than 94.8% (190 US proof)

– Wholly matured in an excise warehouse in Scotland in oak casks of a capacity not exceeding 700 litres (185 US gal; 154 imp gal) for at least three years

2. Scotch whisky must retain the color, aroma, and taste of the raw materials used in, and the method of, its production and maturation.

3. It may not contain any added substances, aside from water and plain (E150A) caramel coloring.

4. It must comprise a minimum alcoholic strength by volume of 40% (80 US proof).

The Production Process

The production of Scotch whisky begins with water. It is for this reason that many of the distilleries still found today are located adjacent to pure water sources such as a river or even a borehole. While transportation is far more effective today, when the vast majority of Scottish distilleries were erected, having to transport large quantities of fresh water proved to be difficult, thereby requiring the distilleries to be built near a plentiful source.

One of the things that separate Scotch whisky from other whiskeys is that the water in Scotland tends to be much softer with significantly lower mineral and calcium contents. For the distilleries located on the west coast of Scotland, particularly on the islands, the water has a much higher peat content due to the water running through peat bogs, which cause it to have a slightly brown tinge. While there is no direct evidence to suggest this natural peat effects the flavor of the whisky, many distilleries believe it to be special, and for that reason, they are very protective of their water supply.

While there is no legal obligation to use Scottish barley to produce Scotch whisky, the vast majority of barley used to make whisky around the world is from Scotland, therefore making it cost effective to utilize local barley.

Once the water is collected it’s used in a variety of ways, the first of which is often to malt the barley. In order to successfully malt barley, the grains are soaked in the water which causes the starch to convert into a type of sugar called maltose which feeds a process known as Germination.

Over the next six days, little shoots begin to grow all over the grains which let the producer know the barley is ready to be dried. To do this, the distillery will elect to use hot air or peat smoke to dry out the grains which stop further growth of the shoots and prevents it from rotting. While the majority of distilleries now purchase their barley pre-malted, there are still a small handful of producers that choose to malt the barley from scratch. Despite the process being painstaking and lengthy, distilleries such as The Balvenie and Highland Park view it as a tradition and pride themselves on their malting floors.

Now that the barley is properly malted, it gets ground until it resembles something like flour. The water source is again introduced and the mixture is poured into a vessel called the Mash Tun. As the barley mixture steeps in the hot water, the mashing tun separates the solids from the sugars and the process is repeated at least twice more. By the time this part of the production process is completed, the hot sugary liquid, called the Wort is ready to continue being turned into whisky.

The next step in whisky making is called the Fermentation Process. The wort is pumped into a wooden or stainless steel receptacle called the Washback and dried or creamed yeast is added to the mix. Once the yeast is added to liquid, it begins to rapidly multiply using up the oxygen in the washback and creating carbon dioxide. As blades mix the yeast into the wort, over the next 48 hours, the yeast begins to devour the sugars turning the wort into alcohol. The distiller now chooses whether or not to remove the liquid or let it sit for up to another 70 hours which produces a fruitier flavor.

The next step is the actual distillation of the whisky. This is when the alcohol is poured into a copper pot still to undergo a series of two distillations, or in some cases, three. The first distillation called the Wash Still is where the alcohol is heated until it boils and its vapor is condensed into liquid and carried through the coiled pipes. The new liquid is then dumped into cooling vats and is now typically around 28% alcohol. Then, the process is repeated and the spirit is re-distilled until it reaches approximately 70% alcohol. As it distills, the vapor is pumped into a rectifying column, making its way through a water-cooled condenser to the spirit safe. The spirit safe then captures the purest cuts that will eventually mature into Scotch whisky.

What’s interesting to note is that the stills used are often a variety of shapes and sizes. What this does is changes the style of the whisky based on the type of flavor profiles the producer wants in its stock.

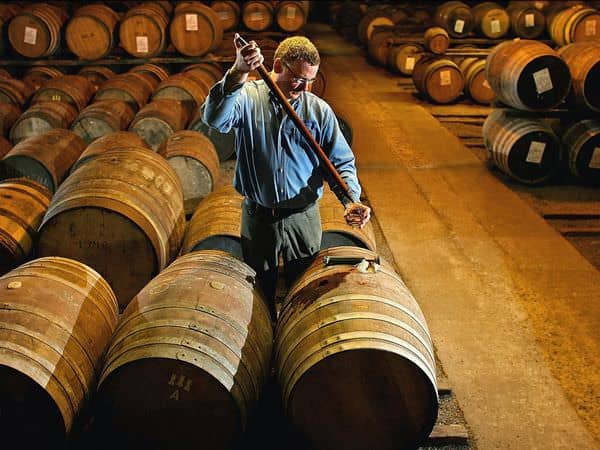

Next, the best cuts of the spirit are slightly diluted with more water and poured into wooden oak casks (usually from bourbon whiskey or Spanish sherry) where the whisky will sit and mature for at least three years, developing a complex range of flavors and aromas as it soaks up the hidden spirits still buried deep in the wooden casks.

After it’s sat for the minimum required length of three years, it is now ready to be bottled or stored longer, increasing its age and complexity.

The Regions of Scotland

Divided into five distinct regions, Scotland produces a variety of whiskeys that take on certain flavor profiles based on the region they’re distilled in.

The Highlands

Known as medium bodied whiskeys, they are typically lighter and more luxurious than their brothers Islay, but stronger than the ones in the Lowlands. Today there are many highland distilleries, some of which include Aberfeldy, Balblair, Ben Nevis, Clynelish, The Dalmore, Dalwhinnie, Glen Ord, Glenmorangie, Oban and Old Pulteney. On the islands, you can find Arran, Jura, Tobermory, Highland Park and Scapa, as well as Talisker still operating today. While many whisky connoisseurs believe the islands should have their own region, they are still technically classified as a part of the highlands.

The Lowlands

Generally considered the lighter and most delicate whiskeys, the Lowland distilleries often produce spirits with very little to no peat. Today the only distilleries still in operation are Auchentoshan, Bladnoch and Glenkinchie. However, a fourth distillery has recently opened called Daftmill, but its first release is still in production and is not expected to be released to the public until sometime in 2015.

Speyside

Home to the most elegant and inspired whiskeys in Scotland, Speyside is also home to the most distilleries in the Country, some of which include Aberlour, The Balvenie, Cardhu, Cragganmore, Glenfarclas, Glenfiddich, Glenglassaugh, The Glenlivet, Glen Moray and The Macallan.

Campbeltown

With the majority of its bottles aged at the 10-year mark, the region is home to just three active distilleries which include Glen Scotia, Glengyle, and Springbank.

Islay

Considered the heavy-hitters of Scotch whisky, these spirits are usually heavily peated, often oily and even sometimes compared to iodine. Islay is home to a current eight distilleries which include Ardbeg, Bowmore, Bruichladdich, Bunnahabhain, Caol Ila, Kilchoman, Lagavulin, and Laphroaig.

Tasting Scotch

Today, Scotch whisky is tasted and enjoyed in a variety of ways. From drinking it neat or on the rocks to mixing it into a range of cocktails, many believe Scotch whisky can be enjoyed any way the consumer can dream. I am not one of them. In my opinion, Scotch whisky is the most perfected spirit on the planet. It is old world craftsmanship at its finest and treating it as you would vodka, tequila or gin is an insult to those who spend their lifetimes pursuing the perfect dram. Therefore, unlike many of my other articles on spirits, I’ve chosen not to provide cocktail recipes in this particular guide.

The Glass

While the majority of Scotch drinkers use a rock glass, in my opinion, there are only two glasses that are acceptable if you actually plan to enjoy your dram in all its glory.

The Copita Nosing Glass

The copita was traditionally used by the Distillery Manager while nosing new make spirits and the Master Blender when nosing a mature whisky that is being considered for use in a blend. Originally called the “Dock Glass” it was developed in the 17th century for merchants to nose the spirit or wine at the dock before accepting the shipment. Because of its unique tulip shape bowl, it allows you to swirl the spirit while facilitating the retention of alcohol vapors. Prior to tasting the whisky, the drinker will generally cover the glass with its accompanying watch glass cover and allow it to sit for a few minutes. One glass costs about $17 shipped.

The Glencairn Glass

Considered the most innovative whisky glass on the market, the crystal Glencairn glass is an official product specifically designed for Scotch whisky. With a tapered mouth and wide bowl, the quality of the whisky is enhanced allowing the connoisseur to identify hidden aromas and flavors in the spirit. The one negative aspect of the Glencairn is that it has a very short, wide stem, which can cause the whisky to warm from the natural heat of your hand. You can buy it here – a set of 4 costs less than $30.

How to Drink Whisky – The Methods

While many people stack ice cubes in their glass before pouring the whisky overtop, nothing short of adding another liquid could harm your tasting experience more. With each ice cube added, the scotch becomes diluted and cooled, changing the flavor profile and masking the aromas. If you are dead set on drinking Scotch on the rocks, I recommend no more than two ice cubes or else you might as well toss it down the drain. While some companies have begun marketing “ice balls” and “ice bricks”, despite taking longer to melt, these added components still disguise the complexity of the dram.

A recent introduction of soapstone or metal cubes that can be chilled in a freezer has hit the US market by storm. Often labeled as “Whisky Stones”, these small cubes are nothing more than a gimmick that will again alter the spirit, rather than elevate it. A neat accessory to keep in your bar for company, I would strongly suggest procuring the soapstone version as it won’t alter the flavor as much as their metal counterparts.

Historically, judges at spirit competitions would water down their whisky mixing the Scotch with up to an additional 50% distilled water. While many people think this is done to eliminate some of the alcohol content, the fact is that by adding a splash of slightly cool still water, the flavors and aromas of the spirit will be elevated, opening up the spirit and allowing you to properly enjoy your dram. While I don’t recommend diluting your whisky with 50% water, I always suggest adding a splash.

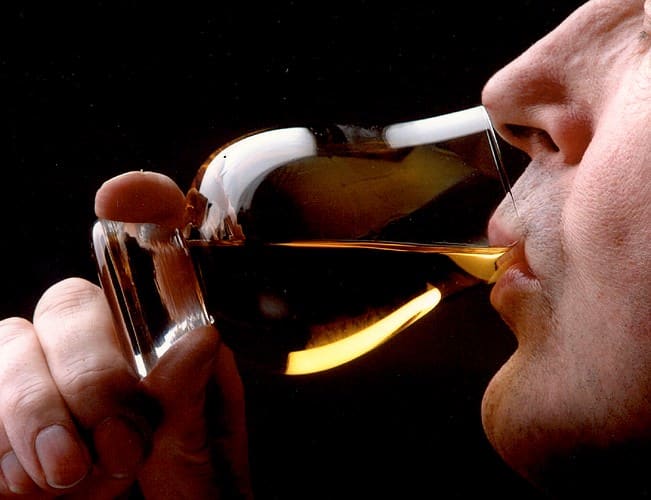

To properly enjoy your dram of Scotch whisky take a clean Copita or Glencairn glass and pour 1/2 oz of whisky into the glass. Swirl it around and pour it down the sink. While it may seem like a waste of good Scotch, and it is (unless you use it for cooking), it also will act as a purifier eliminating any odors or flavors already in the glass that could alter the taste or aroma of your dram. After all, as any cigar aficionado knows, even tap water can change the taste of a cigar, or in this case a Scotch.

Next, pour yourself a glass of whisky. Be careful to hold the glass from its base and not the bowl to ensure your hand doesn’t warm the spirit as it’s poured in. Next, swirl the whisky in the glass and examine its appearance. While the appearance won’t tell you a great deal about the spirit, you want to focus on two key things.

First, is the spirit cloudy? A cloudy spirit will indicate that the whisky has not undergone chill filtration. The purpose of chill filtration is to conform whisky so that there is no cloudiness once water is added. However, a spirit that is cloudy tends to offer an enhanced element of flavor and should be regarded as such. The second and most important reason for visually examining your whisky is to look at its “legs”. After swirling the whisky in its glass, you’ll notice fine beads that will form on the sides of the glass. The legs then slowly ooze back into the glass forming lines called “legs” as they move. The thicker and slower than the legs move, the more vivacious and bold the whisky.

Now that you’ve examined your dram, hold the glass up towards your nose, take a deep breath in through your mouth and your nose inhaling and appreciating it’s complex aromas. Be sure not to bring the glass too close, as the strength of the alcohol can often numb a novice’s senses. Then, take it down and swirl it. Repeat this process at least three times, each time bringing the glass closer to your nose and breathing in more through your nose and less through your mouth. By the final nose, you should allow the rim of the glass to pocket your nose and with your mouth closed, breathe in as the spirit engulfs your senses. By following these steps you’ll notice that the aromas change with each nose. This is the sure way to properly appreciate a fine whisky and to ensure that it doesn’t go to waste and that you get to experience each of its divine and complex aromas.

Next, add a splash of pure still water that’s slightly cool and take your first taste of the spirit. As it hits your tongue swirl and splash it around every part of your mouth. Let it touch your cheeks, the roof of your palate and the bottom of your mouth under your tongue. Allow it to stream in front of your teeth and touch your gums and the inside of your lips. Then let it sit in the middle of your mouth before slowly swallowing the spirit. It’s this method that ensures you’re able to taste all of its complexity, understand its diverse flavor profile and appreciate its aged perfection. Then take a big deep breath and you’ll be eager to try some more.

Video – The Story of Whisky

Recommended Whiskies

Scotch whisky has long been my favorite spirit. On any given evening you can usually find me in my living room enjoying a dram or two as I listen to my records or watch an old movie. This list, while partial, are a few of my favorite whiskeys, all of which I highly recommend.

Btw, to learn how all these different areas and names are pronounced properly, take a look here.

If you are looking for tasting notes by an experienced Scotch whisky drinker including value for money and point ratings, check out www.whiskymusings.com

The Highlands

Ice Balls look very elegant in a glass – but many prefer to drink it without ice – all that matters is what you like

The Dalmore King Alexander III (one of my favorite bottles in the world)

The Dalmore Cigar Malt Reserve (this Scotch pairs perfectly with a medium to full bodied cigar)

Jura Superstition (press your palm against the logo for good luck)

Highland Park 12 Year

Scapa 16 Year

Talisker 18 Year

The Lowlands

Auchentoshan Three Wood (no peat, very delicate and quite inexpensive. A perfect introduction to Scotch whisky)

Glenkinchie 12 Year

Rosebank 12 Year

Speyside

The Macallan Fine Oak

The Macallan 12 Year (while there are many incredible, older bottles, the 12 year is my nightly dram)

The Macallan 25 Year

Scotch & Cigars go well together – although most scotch enthusiasts won’t drink it with ice, some prefer it that way

Aberlour 12 Year (probably the best bottle in its low price point)

Aberlour A’bunadh

The Balvenie Doublewood (the first Scotch I ever tried and one I keep going back to)

Islay

Bowmore 18 Year

Lagavulin 16 Year (one of my favorite bottles from Islay)

Caol Ila Moch

Laphroaig 12 Year

Campbeltown

Glen Scotia 12 Year

Springbank 10 Year

Where to Buy Whisky

Unfortunately, prices and availability really depend on where you live. For example, a 12 year old bottle of Macallan could cost half the price in the United States as it may in parts of Canada, not to mention other countries around the world. Trying to list a reliable whisky source in every country would be impossible because there is no way for me to test all of them. Hence we just list a few hoping most of you will find these links helpful.

The Scotch Whisky Association: the name says it all – contact them if you want to find more sources to buy

Master of Malt: UK based online store, ship to many countries

The Whisky Exchange: UK based online store, ship to many countries

The Whisky Barrel: U.S. based ships worldwide

Love Scotch: U.S. based online store specialized in Scotch

Scotch Whisky Auctions: the name says it all

Caskers: Crafts Spirits

Alexander & James: German online store with gift service

Conclusion

Scotch has and I presume will always be a spirit that one either loves or hates. While a taste for it can be developed over time, typically the most common palate development occurs amongst gentlemen who already enjoy the taste and simply grow to appreciate the varieties.

I would highly recommend that if you’ve never tried Scotch whisky before, that you begin with a gentler, more subtle bottle such as the Auchentoshan 12 year or the Dalwhinnie 15 year, and not with a dram of Lagavulin or Laphroaig.

One final tip for the Scotch connoisseur is to always keep a few basics on hand. This way should you have company over, if they are inclined to try a dram of Scotch but don’t have the appreciation for it, rather than wasting a remarkable whisky on a plebeian’s palate, I always keep a bottle of 12-year-old Glenlivet and Glenfiddich in my bar. That way you can save the premium whisky for those who will truly enjoy it.

If you enjoyed this guide, you should also take a look at our Bourbon and Brandy guides or you could look up other articles in our spirits and cocktail guide.